Inside the SQL Server 2012 Columnstore Indexes

May 29th, 2012Columnar storage has established itself as the de-facto option for Business Intelligence (BI) storage. The traditional row-oriented storage of RDBMS was designed for fast single-row oriented OLTP workloads and it has problems handling the large volume range oriented analytical processing that characterizes BI workloads. But what is columnar storage and, more specifically, how does SQL Server 2012 implement columnar storage with the new COLUMNSTORE indexes?

Column Oriented Storage

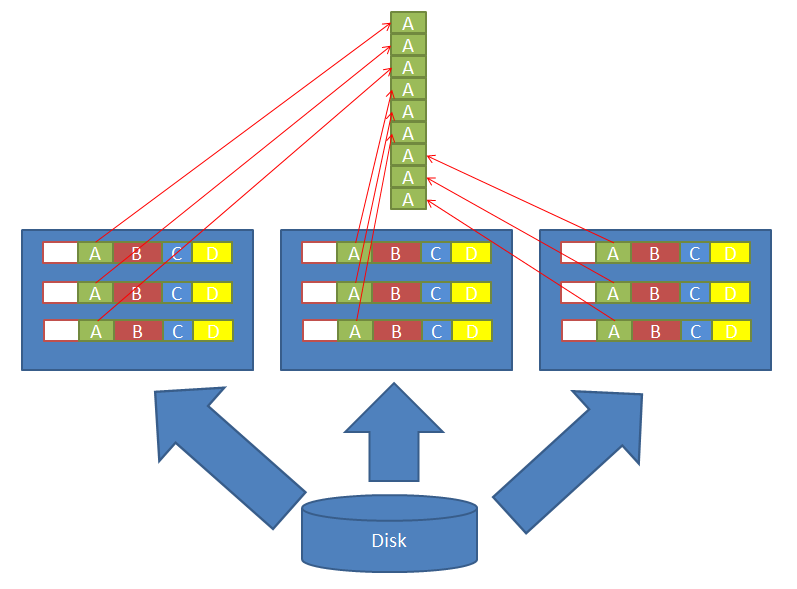

The defining characteristic of columnar storage is the ability to read the values of a particular column of a table without having to read the values of all the other columns. In row-oriented storage this is impossible because the individual column values are physically stored grouped in rows on the pages and reading a page in order to read a column value must fetch the entire page in memory, thus automatically reading all the other columns in the row:

This image shows how in row oriented storage a query that only needs to read the values of column A needs to pay the penalty of reading the entire pages, including the unnecessary columns B, C, D and E, simply because the physical format of the record and page. If you’re not familiar with the row format I strongly recommend Paul Randal’s article Inside the Storage Engine: Anatomy of a Record.

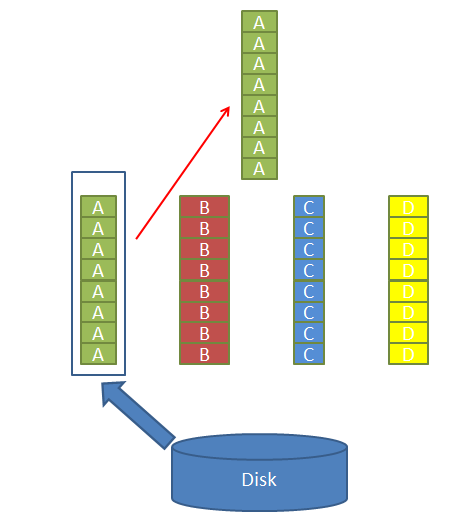

By contrast the column oriented storage stores the data in a format that groups columns together on disk, so reading values from a single column incurs only the minimal IO needed to fetch in the column required by the query:

The most common question I hear often when columnar storage is how is a row stored?. In other words, if we store all the values of a column together, then how do we re-create a row? Ie. if the column Name has the values ‘John Doe’ and ‘Joe Public’, while the Date_of_Birth column contains values ‘19650112’ and ‘19680415’ then when was John born, and when was Joe? The answer is that that the position of the value in the column indicates to which row it belongs. So row 1 consists of the first value in Name column and first value in Date_of_Birth, while row 2 is second value in each column and so on.

By physically separating the values from individual columns into their own pages the engine can read only the columns needed. This reduces the IO for queries that:

- read only a small subset of columns from all the columns of the table (no SELECT *)

- read many rows (scans and range scans)

Columnar storage reads from disk only the data for the columns referenced by the query

Not surprisingly this type of queries is the typical BI query pattern. Note that a column qualifies as ‘read’ not only if is projected in the result set, but also if is referenced in the WHERE clause, or in a join, or anywhere else in the query. Typical BI queries aggregates fact values over large ranges defined by some dimension subsets (eg. “sum of sales in the NW region in Sep.- Nov. period”) and thus they tend to create exactly the queries that the columnar storage loves. The fact that BI workloads use a pattern of queries that references only few columns but many rows, combined with the ability of the columnar storage to read from disk only the columns actually referenced by the query is the first and foremost advantage of the column store technology.

An OLTP workload by contrast tends to read entire rows (all columns) and only one or very few rows at a time. Columnar storage loses its appeal in OLTP workloads and in fact the columnar storage can be significantly slower than row oriented storage for OLTP workloads.

Compression

Because column oriented storage groups values from the same column together there is a new beneficial side effect: data becomes more compressible. Compression can be deployed on row-oriented storage too, see Page Compression Implementation, but with column oriented storage the data is more homogenous, as it contains only values from a single column. Since compression ratio is subject to the data entropy (how homogenous the data is) it follows that columnar storage format is more compressible than the same data represented in row oriented storage format.

Columnstores target large datasets for which compression yields most benefits

Since the columnstore format is targeted explicitly at BI workloads and large datasets, it is justifiable to invest significantly more development effort into enhancing compression benefits: deploy several alternative compression algorithms for the engine to choose from, leverage operations directly in the compressed format w/o decompressing the data first. Row oriented storage have to strike a balance between compression benefits and its runtime cost in consideration of the typical OLTP workload.

Columnstores embrace compression fully and go to great lengths into achieving high compression ratio because in the expected BI workload the savings in IO from better compression more than offset the runtime CPU loss. The individual compression techniques vary between various columnar storage implementation, but your can make a safe bet that some common techniques are used by most implementations:

In addition domain specific compression is used, leveraging the knowledge of the types and values being stored. For example Wikipedia mentions the benefits of sorting the data in order to yield better compression:

To improve compression, sorting rows can also help. For example, using bitmap indexes, sorting can improve compression by an order of magnitude.[6] To maximize the compression benefits of the lexicographical order with respect to run-length encoding, it is best to use low-cardinality columns as the first sort keys.

Note that I am not saying to apply the advice from above mentioned Wikipedia article directly to SQL Server 2012. Specifically columnstore indexes do not require to ‘use low-cardinality keys first’, the order in which you specify keys in SQL Server 2012 columnstore indexes is irrelevant.

Batch Mode Processing

Iterating over hundreds of virtual function calls for each row processes is EXPENSIVE

Reading only the data for the columns referenced by the query and extensive use of compression are techniques used by all columnar storage engines. But SQL Server 2012 also brings something new: a completely new query execution engine optimized for BI queries. To understand why this was necessary and why it has a big performance impact one needs to understand first how query processing works on SQL Server. Paul White has a good series of introductory articles into query processing starting with Query Optimizer Deep Dive – Part 1 and I recommend these articles if you want a deeper introduction into SQL Server query processing. For our purposes it suffices to understand that a query execution consists of iterating over a tree of operators. Query execution is basically a loop that takes the query execution tree top operator and calls a method called GetNextRow until the methods returns end-of-file. This top operator in turn will have child operators on which it calls GetNextRow to produce the data, and these child operators have further child operators and so on and so forth, all the way to the bottom of the tree operators that implement actual physical access to the data. Whether is a simple scan, a seek, a nested loop join, a hash join, a sort, a where filter, any operator behaves the same. Which also implies that this GetNextRow call is a virtual function call. Sometimes these execution trees can be hundreds of operators deep, which means that there will be hundreds of virtual function calls in order to produce one row, followed by again hundreds of calls to produce the next row, then again for the next row and so on. For the analytical workload of OLTP this is not a big deal, since queries are supposed to produce only a few rows and iterate only over small range of the data (a direct seek or a small range scan). But analytical BI queries, even if they produce a small result set containing aggregates, need to scan extremely large sets of data and the cost of traversing deep execution sub-trees to retrieve rows one by one quickly adds up, specially when the calls are all going through a v-table indirection.

Batch mode execution amortizes the cost of calling the operators by requesting many rows in a single call

Enter the new batch mode operators. In batch mode instead of calling a function that returns one row at a time, the query operators call a function that returns many rows at a time: a batch. The benefits of doing so are not obvious for non-programmers, but believe you me, this can result in speed improvements of 2 and even 3 orders of magnitude.

But batch mode execution requires everybody to play the same tune: all operators have to implement the batch mode execution. Row mode operators cannot interact with batch mode operators nor the other way around. For best performance a query plan has to run in batch mode from top to bottom. Since not all operations were implemented in batch mode by the time SQL Server 2012 RTM shipped, sometimes there will be restrictions that prevent batch mode execution. The Query Optimizer can resort to a conversion operator from batch mode to row mode and it can create plans that have sub trees in batch mode even if the upper part of the tree is in row mode. This mixed mode can still yield significant performance improvements, provided that most data processing still occurs in batch mode (eg. aggregation occurs in batch mode and the result of aggregation is consumed in row mode). Eric Hanson has some very useful tricks for how to achieve batch mode processing in some edgier conditions at Ensuring Use of the Fast Batch Mode of Query Execution. Most tricks rely on splitting the query in two, a subquery that does the bulk of the work in batch mode and then project aggregated results into a an outer query that uses some non batch mode friendly operator like OUTER JOIN, NOT IT, IN, EXISTS, Scalar Aggregates or DISTRINCT aggregates.

SQL Server 2012 Columnar Storage

COLUMNSTORE indexes use the same xVelocity technology as PowerPivot

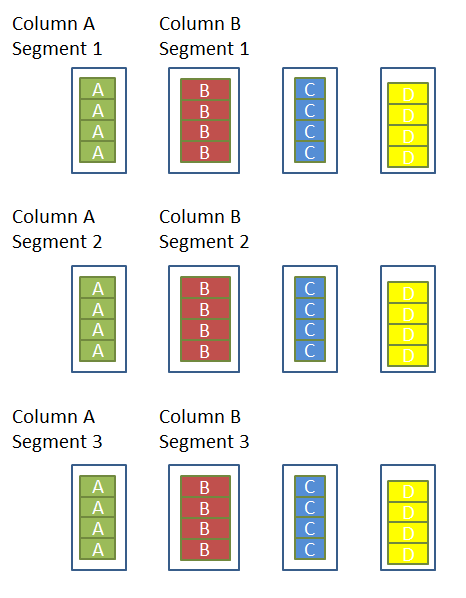

Prior to SQL Server 2012 the columnar storage technology offer from Microsoft was restricted to the BI analytical line of products: Power Pivot and Microsoft SQL Server Analysis Server. Both of these products use xVelocity (formerly known as Vertipac) to create highly compressed in-memory columnar databases. The COLUMNSTORE index of SQL Server 2012 uses the same technology, but adapted to the SQL Server product, specifically to the SQL Server storage and memory model. MOLAP servers store the entire columnar database as a single monolithic file and load it entirely in memory. Such an use pattern would not work along with the complex memory management of the SQL Server buffer pool. Besides, the storage options of SQL Server are capped at the maximum of 2GB size of a BLOB value and that would make for a really small columnar storage database. So COLUMNSTORE indexes instead use the xVelocity technology on smaller shards of the data called segments:

A segment represents a group of consecutive rows in the columnstore index. For example segment 1 will have rows from 0 to row number 1 million, segment 2 will have rows from 1000001 to 2000000, segment 3 from 2000001 and so on. Each column will have an entry for each segment in sys.column_store_segments. Note that at the time of writing this the MSDN entry says “Contains a row for each column in a columnstore index” which is incorrect, it should say “Contains a row for each column in each segment in a columnstore index”. I have talked before about how columnstore indexes store data in the LOB allocation unit of the table, see How to use columnstore indexes in SQL Server. Each column segment will be a BLOB value in this allocation unit. In effect you can think about sys.column_store_segments as having a VARINARY(MAX) column containing the actual segment data, with the amendment that the storage of this VARBINARY(MAX) column comes from the columnstore index LOB allocation unit and not from the sys.column_store_segments own LOB allocation unit. So it should be clear now what is the main limitation in a column segment: it cannot exceed 2GB in size, since this is the maximum size of a VARBINARY(MAX) column value. A column segment is uniformly encoded: for example if the column segment uses a dictionary encoding then all values in the segment are encoded using a dictionary encoding representation.

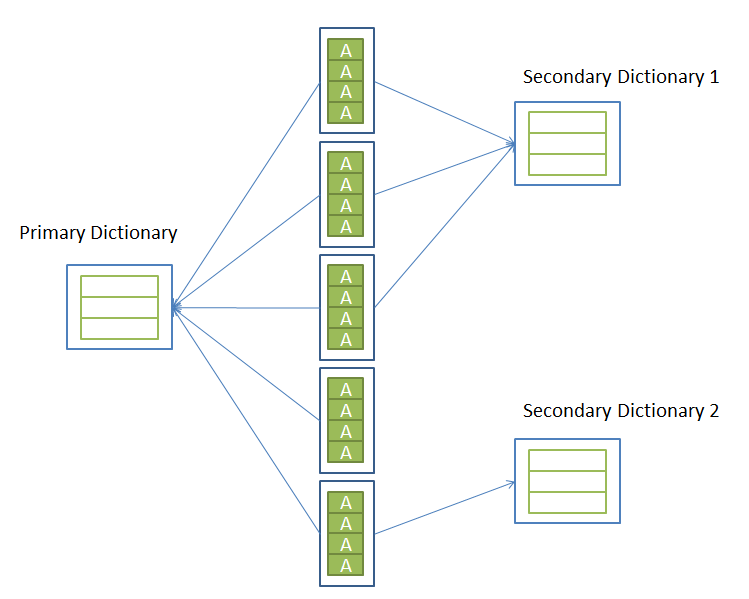

Dictionaries are always used to encode strings and may be used for non-string columns that have few distinct values

Besides column segments a columnstore consists of another data storage element: dictionaries. Dictionaries are widely used in columnar storage as a means to efficiently encode large data types, like strings. The values stores in the column segments will be just entry numbers in the dictionary, and the actual values are stored in the dictionary. This technique can yield very good compression for repeated values, but yields bad results if the values are all distinct (the required storage actually increases). This is what makes large columns (strings) with distinct values very poor candidates for columnstore indexes. Columnstore indexes contain separate dictionaries for each column and string columns contain two types of dictionaries:

- Primary Dictionary

- This is an global dictionary used by all segments of a column.

- Secondary Dictionary

- This is an overflow dictionary for entries that did not fit in the primary dictionaries. It can be shared by several segments of a column: the relation between dictionaries and column segments is one-to-many.

The image above illustrates the use of primary and secondary dictionaries. All segments of the column reference the primary dictionary. Segments 1,2 and 3 use the secondary dictionary with ID 1. Segment 4 does not need a secondary dictionary and segment 5 uses the secondary dictionary with ID 2.

Information about the dictionaries used by a columnstore can be found in sys.column_store_dictionaries catalog view. Again, at the time of writing the MSDN explanation on it is wrong, it should read “Contains a row for each dictionary in an xVelocity memory optimized columnstore index”. Information about which dictionary is used by each segment is available as the primary_dictionary_id and secondary_dictionary_id columns in sys.column_store_segments. Remember that:

- Not all columns use dictionaries.

- Non-string columns may use a primary dictionary.

- A string column will always have a primary dictionary and some segments may use a secondary dictionary.

The storage of the dictionaries is very similar to the storage of the column segments: think of it as a VARBINARY(MAX) column in sys.column_store_dictionaries with the actual physical storage provided by the columnstore LOB allocation unit. The same 2Gb size limit limitation that applies to column segments applies to dictionaries.

Segment Elimination

The min and max value of the data in the segment is stored in metadata, which enables the query processing to skip entire segments

The sys.column_store_segments catalog view shows the columns min_data_id and max_data_id which are metadata about the min and max values stored in the column segment. The values in the catalog view cannot be interpreted directly because they have to be decoded based on the column segment encoding type and perhaps consider the dictionary used. Knowing that a column segment contains only values between the min and the max, query processing can decide to skip an entire segment. Since the min and the max are stored in the metadata it is not necessary to even load the segment from disk, saving both IO and processing CPU. Segment elimination thus works much like partition elimination works in classic row stores (BTrees and Heaps), but the columnstore segment elimination is actually better:

- Columnstore segments min and max values are stored in metadata for every column. Partition elimination works only on predicates that reference the partitioning column, but segment elimination works on any predicates that reference any column.

- Columnstore segments min and max values are from the actual data in the segment. Partition elimination works not on actual data values but on partition definition boundaries, which may be much larger than the actual values present in the partition. Thus segment elimination kicks in more often.

- Segments are much smaller than partitions, so simple probabilities tell us that more small segments will be eliminated where a partition would had to scan the entire partition, even when much of the data does not qualify.

Where segment elimination comes to shine is time series. The nature of time series implies that segments will tend to have one column (the date column) with very narrow range of values, and each segment will have a different range of values: segment one will have sales from Jan. 1st, segment 2 will have from Jan. 1st and 2nd, segment 3 from Jan. 2nd and 3rd, segment 4 from Jan. 3rd only and so on. So queries that predicate a time range (which are the overwhelming type of queries on time series) will benefit massively from segment elimination, reading and scanning only a small subset of the data. But be aware that in order to get this benefit the columnstore index must be built in a way that results in the data being ordered by the time column. Remember that columnstore indexes have no key. The gritty details are described in Ensuring Your Data is Sorted or Nearly Sorted by Date to Benefit from Date Range Elimination. For more complex scenarios that involve multiple dimension you should consider aggregating the values into complex values, see Multi-Dimensional Clustering to Maximize the Benefit of Segment Elimination. As a side node I find interesting that similar technique of aggregating values into complex keys applies to such a different technology as SimpleDB, see SimpleDB Essentials for High Performance Users.

Of course if you have a partitioned columnstore index then the query can leverage both partition elimination and segment elimination.

How to use Columnstore Indexes

Columnstore indexes support only scan operations

If you remember one thing from this article is this: a columnstore index is not an index. In the traditional row storage an index is a b-tree structure which supports seek and range scan operations. Columnstores are much more like the row store heaps and supports only end-to-end scans. They do not have a key and do not offer any order of rows. Yet, on large data sets, they can offer exceptional performance for analytical workloads due to the factors mentioned above: read only for the columns referenced by the query, high compression, segment elimination and fast batch mode processing. I’ve seen dramatic examples of queries that on highly optimized row storage could not run below 17 seconds and a columnstore could run the same query in under 18 milliseconds! Performance improvements of factors of higher 10s and even 100s times are the norm you should be looking for with columnstores.

Add all columns to the columnstore index

Comparing with traditional row store indexing strategies, the columnstore indexing rules are straight forward: pick a large table that is usually the fact table in a star schema data warehouse and add a columnstore index that includes every column. Without key order, ASCENDING or DESCENDING clauses, fill factors, filtered indexes, INCLUDE columns or any other of the whistles and bells of row store indexes, the decision is much simpler. Consider the columnstore index as an alternative to the base table.

Of course the biggest columnstore draw back with the SQL Server 2012 release is the inability to update data. Once a columnstore index is added to a table the table becomes read-only. The best way to circumvent the problem is to use the ability to do fast partition switch-in operations, which allow for partitioned columnstore indexes to be updated. See How to update a table with a columnstore index.

Recommended Reading

The SQL Server social Wiki on MSDN has some excellent resources for columnstores:

SQL Server Columnstore Performance Tuning

SQL Server Columnstore Index FAQ

Achieving Fast Parallel Columnstore Index Builds

Work Around Performance Issues for Columnstores Related to Strings

Use Outer Join with Columnstores and Still Get the Benefit of Batch Processing

Using Statistics with Columnstore Indexes

“Prior to SQL Server 2012 the columnar storage technology offer from Microsoft was restricted to the BI analytical line of products: Power Pivot and Microsoft SQL Server Analysis Server.”

The Analysis Services Tabular engine, which also uses the xVelocity storage engine, only appeared in SQL Server 2012 as well.

[…] INSIDE THE SQL SERVER 2012 COLUMNSTORE INDEXES Share this:EmailPrintFacebookShareDiggRedditStumbleUpon […]

@Gonsalu is half right, but is forgetting that the 2008 R2 version of Analysis Services could be installed in tabular mode when backing PowerPivot-in-SharePoint.