How to shrink the SQL Server log

July 27th, 2012I noticed that my database log file has grown to 200Gb. I tried to shrink it but is still 200Gb. How can I shrink the log and reduce the file size?

The problem is that even after you discover about DBCC SHRINKFILE and attempt to reduce the log size, the command seems not to work at all and leaves the log at the same size as before. What is happening?

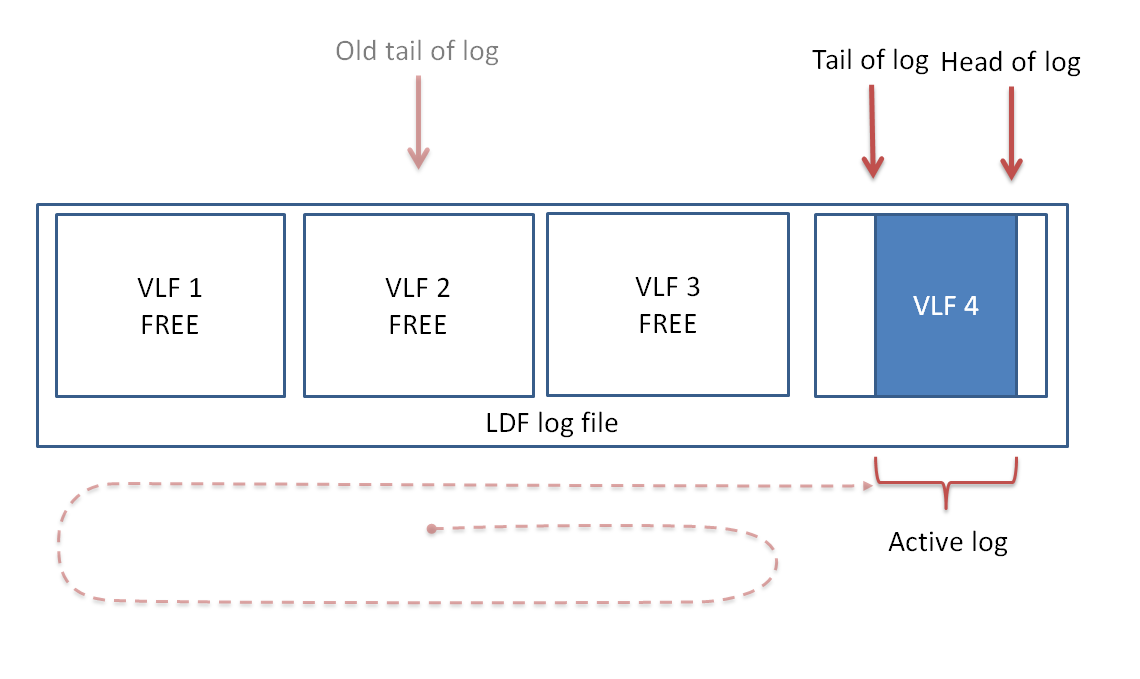

If you look back at What is an LSN: Log Sequence Number you will see that LSNs are basically pointers (offsets) inside the log file. There is one level of indirection (the VLF sequence number) and then the rest of the LSN is basically an offset inside the Virtual Log File (the VLF). The log is always defined by the two LSNs: the head of the log (where new log records will be placed) and the tail of the log (what is the oldest log record of interest). Generating log activity (ie. any updates in the database) advance the head of the log LSN number. The tail of the log advances when the database log is being backed up (this is a simplification, more on it later).

Use DBCC LOGINFO to view the layout of the VFLs inside the log file

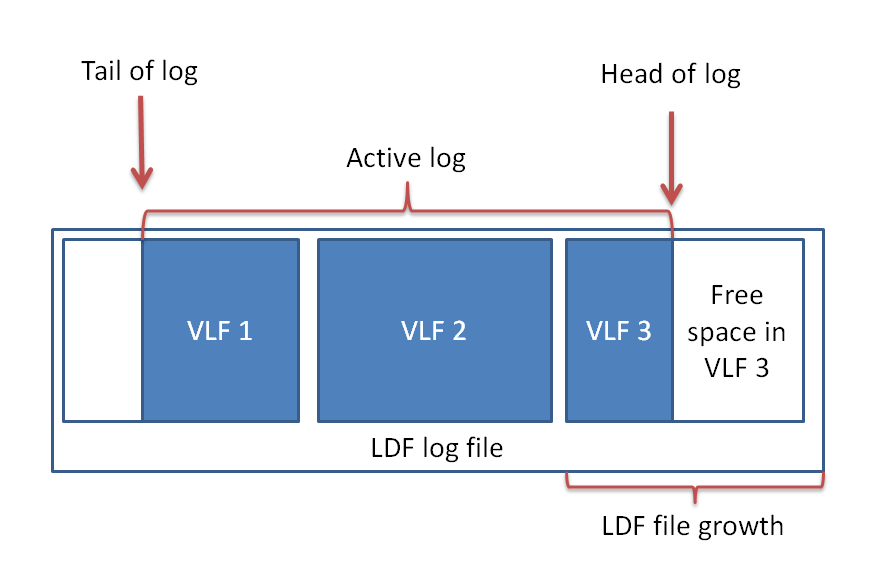

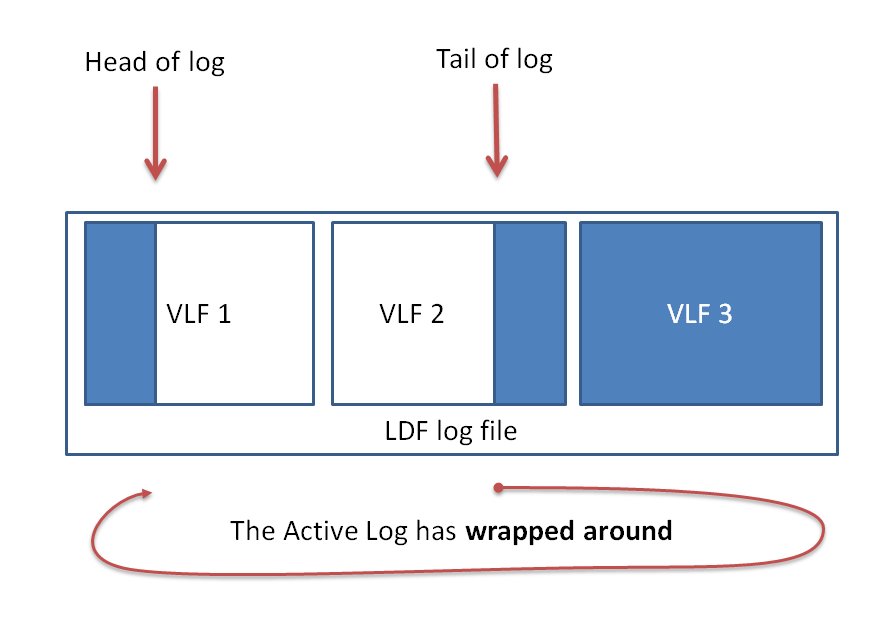

The image above shows as typical log file layout. To understand the layout of VLFs inside your LDF log file use DBCC LOGINFO. The head of the log moves ahead as transactions generate log records, occupying more of the free space ahead in the current VLF. If the current VLF fills up, a new empty VLF can be used. If there are no empty VLFs the system must grow the log LDF file and create a new VLF to allow for more log records to be written. This is when the physical LDF file actually increases and takes more space on disk:

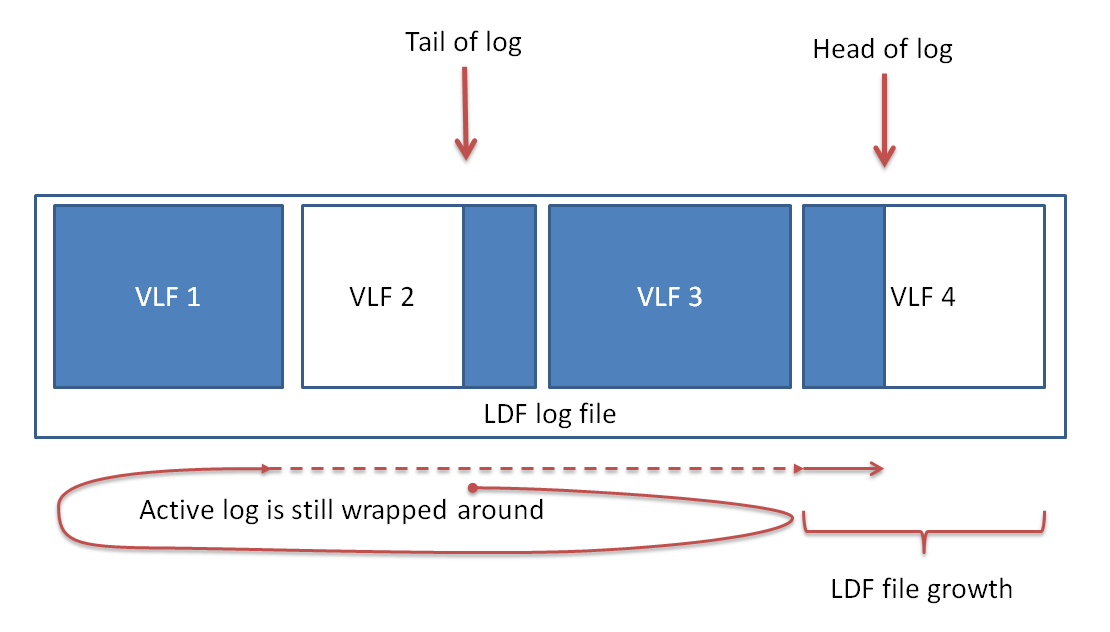

Advancing the head of the log can cause LDF file growth when no free VLFs are available

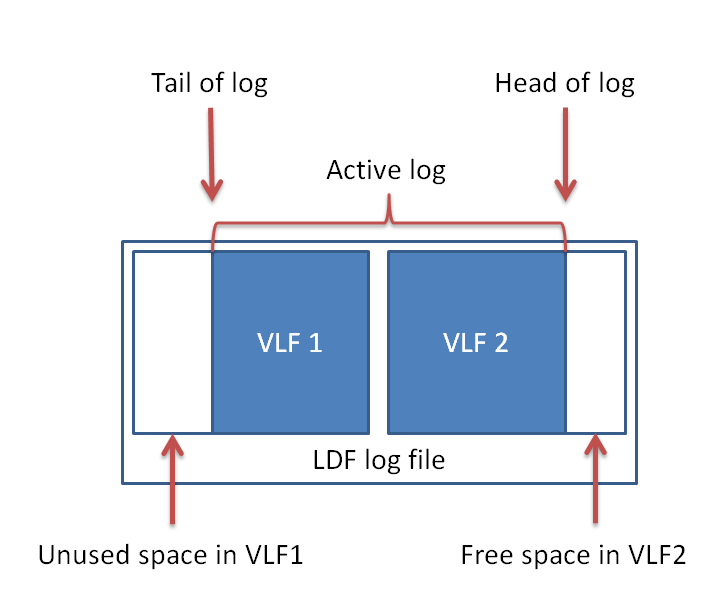

In the image above some more transaction activity resulted in head of the log advancing forward. As the VLF2 filled up, the system had to allocate a new VLF by growing the physical log LDF file. The unused space in VLF1 cannot be used as long as there is even a single active LSN record in it, the What is an LSN: Log Sequence Number article explains why this is the case. If we now take a backup of the log truncation would occur. Truncation is described as ‘deleting the log records’ but no actual physical deletion needs to occur. It simply means the tail of the log will move forward: a database property that contains the LSN number of the tails of the log gets updated with the new LSN number repreesenting the new rail of the log position:

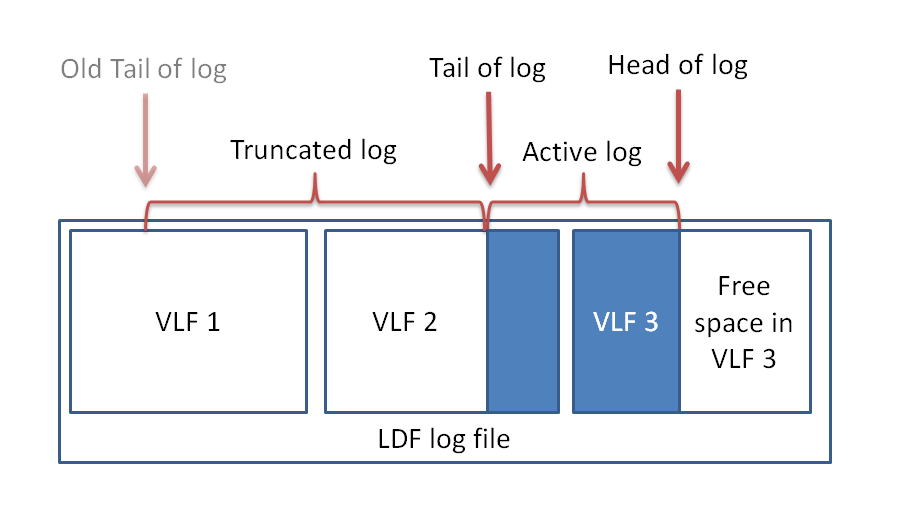

As the head of the log continues to advance due to normal database activity, it now has room to grow by re-using the free VLF 1. This will cause an active log wrap around: the log starts reusing free\ VLFs inside the LDF file and advancing the head of the log no longer causes physical LDF file to grow:

In this configuration if the head of the log continues to advance it has room to grow in the VLF 1. But, unless further truncation occurs, if it fills VLF 1 in order to continue to move ahead the head of the log will require yet again the LDF file to grow in size to accommodate a new free VLF:

If we truncate the log now the tail of the log would apparently follow the path taken by the head of the log and eventual catch up the current head of the log. In effect all that happens is that the database property that contains the LSN which si the current tail of the log gets updated with the new LSN. The apparent ‘path’ is just an effect of the nature of LSN structure.

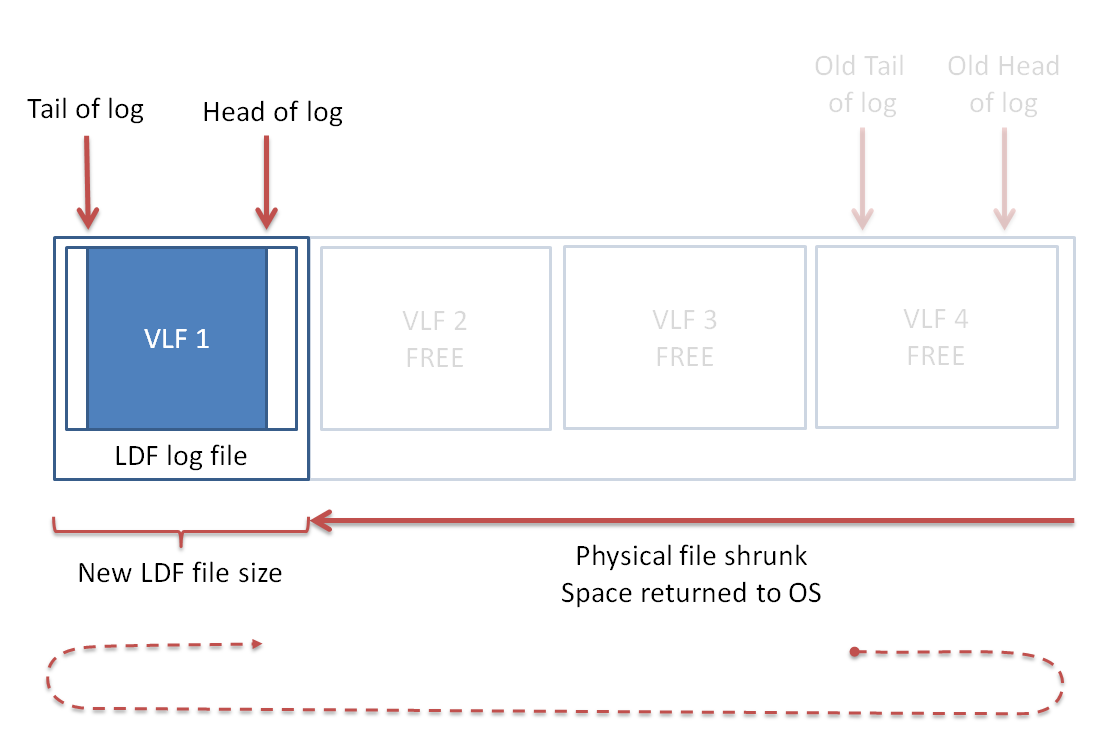

In this state the LDF file contains 3 empty VLFs and only a small active log portion. However, the physical LDF file cannot be reduced in size, any attempt to shrink the file will fail. As a general rule a file (any file) can only be shrunk (reduce in size) by removing data at the end of the file (basically by reducing the file length). Is not possible to ‘delete’ from the beginning of a file or from the middle of a file. Unlike data MDF files, the system cannot afford to move records around in order to free space at the end of the file, remember that LSNs are basically an offset inside the file. The active portion of the log cannot be moved, because there all those records in the active portion of the log would suddenly become invalid.

If the last VLF in a log file is inactive, the log file can shrink

So if the LDF file can reduce its size (shrink) only be reducing its length and active VFLs cannot move it is clear what is the condition when the DBCC SHRINKFILE requires in order to succeed: the last VLF in the file must be free (inactive). Recursively apply this condition to the VLFs left after removing the last one and we have the answer to how much can the log shrink. And this is the explanation why almost always when you care about this information, you are in a bad state in which you cannot shrink the log file. Is just that the typical sequence of events leads exactly to this situation:

- Full recovery model gets enabled on the database

- No maintenance plan is in place and log backups are not taken

- The large log LDF file is noticed

- After a frantic search on internet, the solution of taking a log backup is found

- Shrinking the log fails to yield any reduction in the log LDF file size

This sequence of actions causes the head of the log to advance forward, creating new VLFs as the log file expands. When the situation is detected and the log backups are taken, the tail of the log catches up as truncation (logical freeing) occurs. But in the end the head of the log is located in the last added VLF, which is exactly at the end of the log file. Since the last VLF is active, no shrink can occur, as explained above, despite a large portion of the log file being free (inactive). To make progress in this situation one must first cause the head of the log to move forward so that it fills the last VLF and then it wraps around and reuses the free VLF(s) at the beginning of the file. So, perhaps counter intuitively, you must actually generate more log activity in order to be able to shrink the log file. On an active database this log activity will occur naturally from ordinary use, but if there is no activity then you must cause some. For example, do some updates in a transaction and roll back. Repeat this until the head of the log has wrapped around and is located in the VLFs at the beginning of the file. As soon as this happens, take another log backup to cause truncation which will move the tail of the log forward, following the head of the log and wrapping around. Now the VLFs at the end of the file are inactive and DBCC SHRINKFILE can actually succeed:

DBCC LOGINFO

Here is an example output from running the DBCC LOGINFO command:

RecoveryUnitId FileId FileSize StartOffset FSeqNo Status Parity CreateLSN -------------- ----------------- ------------ ------ ------ ------ ----------------- 0 2 253952 8192 242 0 128 0 0 2 278528 262144 243 0 128 0 0 2 311296 540672 241 0 64 30000000028200477 0 2 262144 851968 236 0 128 34000000025600489 0 2 262144 1114112 237 0 128 35000000010400007 0 2 262144 1376256 238 0 128 35000000023400481 0 2 262144 1638400 239 0 128 36000000013600418 0 2 262144 1900544 240 0 128 36000000036800482 0 2 262144 2162688 244 0 128 73000000037600584 0 2 262144 2424832 245 0 128 74000000009400581 0 2 262144 2686976 246 0 128 74000000034200584 0 2 327680 2949120 247 0 128 75000000013600585 0 2 327680 3276800 248 2 128 76000000001600581 (13 row(s) affected)

This example shows 13 VLFs in the file. 12 are inactive (status is 0) and only the very last one is active (status 2). The active VLF starts at offset 3276800 in the file and has a size of 327680. A quick sneak in sys.database_files reveals that the log file size is 440. The file size is in 8k pages (even for log, although the log file structure has nothing to do with the 8k data page of the MDF/NDF data files) so the file size is 3604480 bytes. Which matches exactly our last VLF ending (3276800 + 327680). So indeed the log file is 3.4 MB in size, from which 3.12 MB are inactive and the last 320 Kb are active (in use by the last VLF). Not that I would ever recommend shrinking a 3.4 MB log, but if we’d try to shrink this file it would yield no results because the very last VLF is active.

Tail of the log

I said before that the tail of the log is moved forward by log backups, but that is a simplification. Advancing the tail of the log is tad more complex because the tail is not a precise LSN: is the lowest LSN of any consumer that needs to look at the log records. Such consumers are:

- Active Transactions

- Any transaction that has not yet committed needs to retain all the log from when the transaction started, in case it has to rollback. Remember that rollback is implemented by reading back all the transaction log record and generating a compensating (undo) action for each.

- Log Backup

- Log backup needs to retain all the log generated until the next log backup runs, so it is copied into the backup file.

- Transactional Replication

- The transactional replication publisher agent has to read the log to identify changes that occurred and have to be distributed to the subscribers.

- Database Mirroring, AlwaysOn

- Both these technologies work by literally copying the log to the partners, so they require the log to be retained until is copied over.

- Other

- If you check the log_reuse_wait_desc column documentation in Factors That Can Delay Log Truncation you will see all the other processes that can retain the log tail, things like CHECKPOINT, an active backup operation, a database snapshot being created, a log scan (fn_dblog()) etc. All these will cause the tail of the log to stay in place (not progress forward).

The tail of the log will be the lowest LSN from any of the LSNs required by the processes above. Whenever the tail of the log advances forward the log is said to be truncated, as described in Transaction Log Truncation.

Further reading

Everything I described in this article was discussed before, there is no original contribution here (maybe the pictures…). This subject is covered very well and here are some links to related articles:

Holy cow! This is a really good explanation of how the transaction log is populated and used.

Thanks for the good article.

John